There are more than 13 million manuscripts held and maintained by UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library (along with hundreds of thousands of maps, rare books, photographs, broadsides, and more) but the majority of those documents have not been digitized or transcribed. This is typical in the world of special collections libraries; the National Archives online catalog, for example, contains more than 455 million digitized pages of records, but that’s just a small percentage of the 13.5 billion total pages held there.

Transcribing primary source documents is time-consuming and requires expertise in deciphering handwriting, recognizing antiquated spelling and abbreviations, and understanding obsolete punctuation, letters, and symbols. Equally important is having a grasp of the historical context of the document being transcribed.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have some experts excited that AI may soon be able to take on this often monotonous task, giving scholars more time to analyze history rather than decrypt calligraphy. “Accurate, trustworthy AI transcription could make centuries of history more accessible, helping today’s researchers decode cursive and translate global narratives instantly,” said Holly Robertson, Curator of University Library Exhibitions. “And it’s a potential gamechanger for digital accessibility.”

The “AI Transcription Winter 2026 OLLMpics”

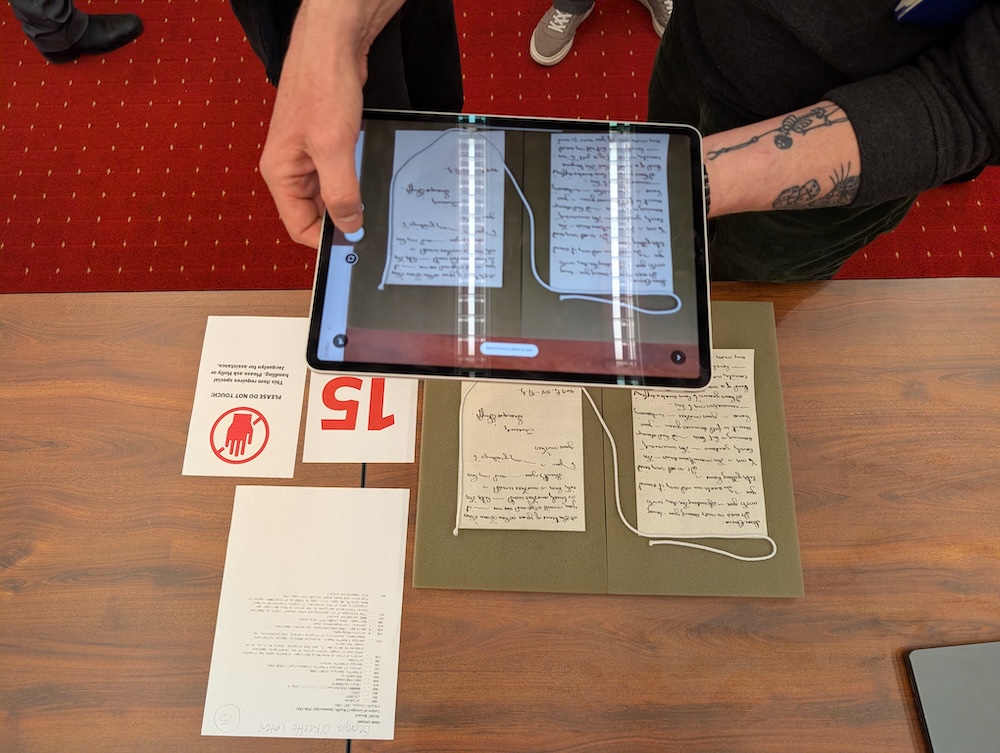

On Jan. 21, Robertson, in partnership with Stan Gunn, Associate Dean for Information Technology, put this theory to the test by hosting what the two cleverly called the “AI Transcription Winter 2026 OLLMpics” (with the “LLM” standing for “Large Language Models”) in the Harrison/Small Auditorium in Special Collections. Robertson chose 15 different documents from the Special Collections archives, offering a span of 600 years of handwriting for analysis and transcription. Participants (dozens of UVA Library staff members) divided into groups of four and then chose a document to photograph and upload to the four major AI transcription tools: ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Copilot.

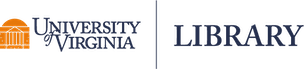

“These were some of our trickiest primary sources: handwritten letters, complicated ledgers, cross-hatched documents, Spanish and Arabic texts, hand-drawn maps, and even a shoe,” Robertson said, referencing the “ruby slipper” sent to former UVA President Teresa Sullivan after her controversial firing by the Board of Visitors in 2012 and later donated to Special Collections after her reinstatement.

Participants were instructed to “disable the use of conversations for creation of training data” with the each of the LLMs, meaning that with these instructions, the AI tools could look at the documents but not absorb the data into their systems. The participants then prompted each LLM to provide an accurate transcription (and, if needed, translation) of their chosen documents, as well as context, meaning, and significance. They were asked to then evaluate the results using a rubric that measured for accuracy of transcription, translation, formatting, and context. With those instructions, Library staffers quickly got to work, and the room was soon buzzing with activity.

Clear winner (and loser)

In one corner, four participants asked the various LLMs to transcribe and analyze the first page of a copy of the Koran from 1800. Dimitri Kastritsis, Librarian for Global Studies, Classics, Middle East and South Asia, is also an active researcher in Middle Eastern history. “I know this one by heart,” he said, referring to Al-Fatiha — the first chapter of the Koran. He watched as ChatGPT transcribed and translated the text, noting that because the Koran is a sacred document, it’s meant to be easy to read.

“So far ChatGPT (from OpenAI) seems to be correct, and it recognizes what it is, being the Koran,” he said. “[The Koran] is written perfectly and therefore it’s easy to transcribe.” He paused. “I’m curious about how many of the lines the AI is seeing and actively transcribing versus how much is based on existing knowledge in LLMs.” Kastritsis was referring to the fact that AI absorbs, or “scrapes” open datasets across the internet (books, webpages, articles) to create “generative pre-trained transformers” (this is the “GPT” in ChatGPT), artificial neural networks that use that scraped data to create new content.

Nearby, another group of librarians tested out LLMs on the “ruby slipper,” finding that the AI failed at deciphering the writing from a still photograph of the shoe but could process a video of it instead. Beside them, a third group had AI transcribe handwritten daybooks of the Richmond Police Guard from 1834-1843. They found that Gemini (from Google) provided the most accurate transcription, while Copilot (from Microsoft) did the poorest job. “Copilot was completely factually incorrect,” said Krystal Appiah, Head of Collection Development for Special Collections. “All of the names it transcribed were wrong.”

This was a common refrain — every group gave low marks to Copilot (descriptions included “useless” and “far and away the worst,” with complaints about Copilot “hallucinating” pages). On the other end of the spectrum was Gemini, with top marks from nearly all the participants. “Gemini did really well — it gave accurate transcription as well as thorough analysis and historical context of the events surrounding our object,” said Stacey Evans, Senior Imaging Specialist and Project Coordinator, about the “ruby slipper.” ChatGPT was ranked second best, and Claude (from Anthropic) came in third.

Where do we go from here?

In a closing discussion, one librarian raised the point that UVA has a license with Copilot and offers it for free to all UVA affiliated users. “I’m interested in how what we gathered here today might be used, given that the University tool [Copilot] was rated the worst,” said Todd Burks, a Teaching and Learning Librarian. Stan Gunn replied, saying that UVA ultimately does not want its community locked in to only one LLM, there is an ongoing pilot program with Anthropic’s Claude and a pilot for ChatGPT and Gemini are in the works.

Library Dean Leo Lo observed some of the session and said it was a great example of the Library serving as an AI hub, where Library staff places a premium on learning and engaging with AI rather than going all in without understanding it first. “Our job right now is to just try this out and share. What do you find useful? What do you not find useful?” AI use in archives is a potentially rich area, he said, as long as librarians maintain responsibility and judgement. “An AI-literate person should apply critical thinking to using this technology.”